ETYMOLOGY AND DEFINITION OF “BONE”

The Greek word for “bone” is ὀστέον (“osteon”); also derivable from Greek “ostrakon” (oyster shell). Proto-Indo-European *h₃ésth₁, Sanskrit अस्थि (ásthi) from wich “ashes” (cremated remains). Cognates include Latin “os” and Old Armenian ոսկր (oskr). Other roots: Hittite “hashtai-“, Avestan “ascu-“ (shinbone), Welsh “asgwrn”, Albanian “asht”.

A thigh bone probably belonging to a young bull, I found on a beach at Bracciano Lake, in Lazio, Italy, which I gilded.

Medicine defines “bone” as a semi-rigid organ that constitutes part of the vertebrate skeleton. Bones support and protect the various organs of the body, produce red and white blood cells, store minerals, provide structure and support for the body, and enable mobility. Bones come in a variety of shapes and sizes and have a complex internal and external structure. They are lightweight yet strong and hard, and serve multiple functions.

THE SYMBOLISM OF BONES

A long lasting relation connects all cultures of the world with the cult of bones from the beginning of time. From a symbolic point of view, bones are often considered as a symbol of mortality, but they also represents permanence beyond death as well as our earthly passage. In some way, bones represent our truest and barest self: they are the frame of our bodies – our home and anchor in the physical world. As minerals, they remind us of our origin from inanimate matter. As adornment bones are usually used as a connection with the dead ones, exorcism of fear, they may also represent aging, self-empowerment, appropriation of the strength of the enemy or the prey.

By virtue of this symbolic power, bones and skeletons have deep significance in our dreaming activity. For instance, ‘being stripped or cut to the bone’ may signify a sudden insight or an attack on your personality, ‘fractured limbs’ may be interpreted as a threat to the foundations of life, and to personal power, ‘broken bones’ may mean weakness in your plans or psychology. Additionally skeletons can sometimes refer to a secret as revealed by the idiom ‘skeleton in the closet’ used to describe an undisclosed fact about someone which, if revealed, would damage perceptions of the person. An “inconvenient truth”, fact or event, kept secret for so long that it has decomposed to bones.

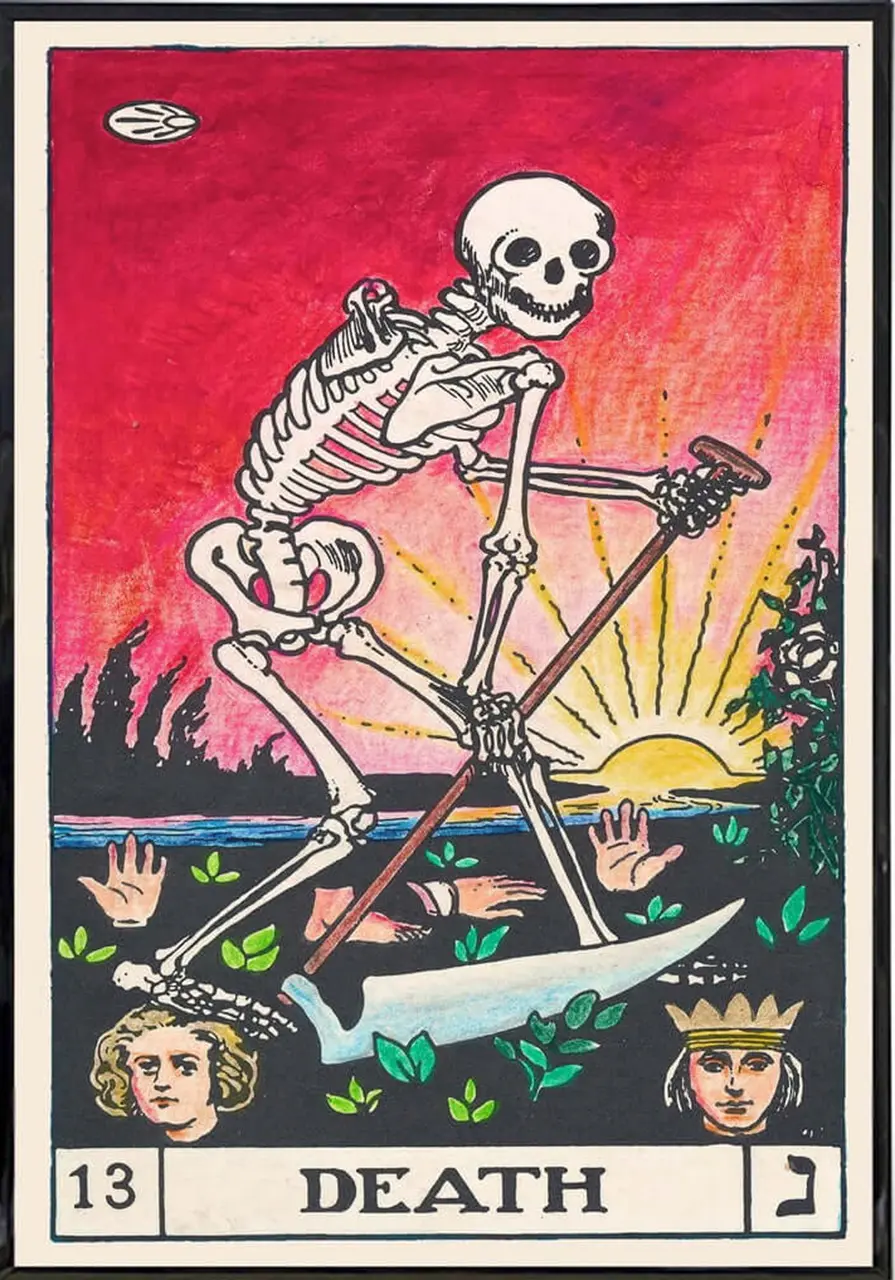

Death Tarot card.

In the greatest arcades of the Tarot, Death, the number thirteen, has predominantly a positive meaning: it represents change, transformation, as a life cycle stage, it therefore fits into a personal pathway, and brings renewal. The skeleton is a memento mori, the sickle symbolizes the crop season and therefore, for the messes, it is the end of a phase and the beginning of another. This arcane is meant as rebirth, a moment in which it is necessary to change, to close with the past and look up to the future. It may also be an invitation to grow, to spiritually evolve, to mature, linked to the need to make a square clean of something, or simply to prepare for radical changes.

BONES FROM CUSTOMS TO ARTS

The fear of death and the desire to see/understand its mystery, have always stimulated human thought and actions and are actually at the origin of the culture. Since the Neolithic, the scarneficated skull was detached from the dead body to turn it into a sculpture that could remind the person alive. The famous skull of Jericho, dating back to 7000 BCE, even holds a smiling expression, thanks to a couple of shells posed in place of the eyes. It tells of the desire of immortality, of the will to exorcise death, of the hope in a better afterlife. This custom is still universally valid today and makes our perception of the world almost magical.

A plastered skull from the ancient city of Jericho in Palestine 7000 BCE.

In Latin-America, bones and skeletons are part of the landscape, of what surrounds you, as well as death, an essential part of personal fantasy and culture (see Día de Muertos), in countries where you feel that life is hanging on a thread and it is therefore best to face it with a smile or irony. In Europe, and Western culture in general, from the industrial revolution, death has been considered much obscene to sex and its reproduction actually a taboo. Life and death are clearly separate. Where life is celebrated, death is censored, although in other times it was not so.

In the Middle Ages or the Renaissance, the depiction of death was indeed not a cause of clamour. Just think of the ossuaries that spread throughout Europe, like Santa Maria della Concezione dei Cappuccini in Rome, the Sedlec Ossuary in the Czech Republic or the Capela dos Ossos in Évora, Portugal. In figurative art, the privileged subjects of the art depiction were crucifixions, deposition, and chronicles of martyrdom: the most erratic and cruel deaths were a direct show on the public squares and the taste of the horror was something absolutely acceptable.

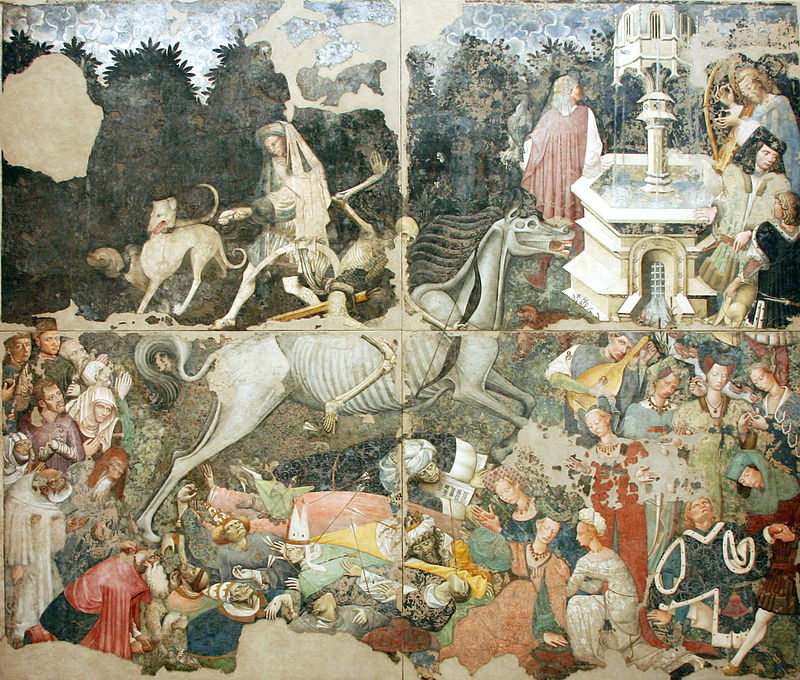

The Triumph of Death (1446) – Pieter Bruegel the Elder, Palazzo Abatellis, Palermo (Italy).

Today the “deadly theme” has become popular again, in art an not only. Is it just scandalous, shocking merchandising, to make much money as quick as possible? A traditional way to ironize with the “huesuda señora” (the bony lady) that we all, sooner or later, must face? Or – if artists are the forerunners of the times – it is also a way to exorcise the phantom of our imminent extinction and invite to action?

One of the artists closest to this esoteric vision of life, death, and temporality is the Italian magician and artist Gino De Dominicis. In “Il tempo, lo sbaglio e lo spazio” (Time, Mistake, Space) (1969) the skeleton figures of a dog and the man who keeps him on the leash with the roller-skates at his feet are the metaphor of the tempus fugit while, at the same time, suggesting an impressive vital energy. A key to this work is found in the “Lettera sull’Immortalità” (Letter on Immortality) the artist wrote in 1970: «Since man cannot intervene directly on himself to stop the inexorable advance of his own ‘internal time’ and prolong his own life span, he has invented the means to make it that much faster: by intervening in space, he has indirectly managed to influence time. This operation might be justified only if space were finite and our imagination limited. Unfortunately, however, it is simply a palliative and a terrible mistake.”». In his vision, human being is always trying to overcome the limits of his own mortality even though he is fatally besieged in a fate of death. For this reason art becomes an exercise of freedom.

“Il tempo, lo sbaglio e lo spazio” (1969) – Gino De Dominicis Palazzo delle Esposizioni, Rome, 2014.

De Dominicis’ esoteric tension is even more evident in the “Cosmic Magnet” (1988), the 24-meter-long sculpture-skeleton exhibited for the first time in Grenoble in 1990. Actually De Dominicis wanted to cover it entirely with pure gold, but even so naked, gently resting on the ground, with its beak nose in the air and that golden antenna-rod (or gnomon?) in perfect balance on the last distal phalanx of the middle finger of the right hand, entertains not only a conversation with the cosmic space, but also with us little terrestrials so busy with our futile daily affairs and forgetful of existential issues, which are universal.

“Cosmic Magnet” (1988) – Gino De Dominicis

Another huge skeleton around the world is “Habibi” by French-Berber-Algerian artist Adel Abdessemed, who in 2004 created this 17-meter-long skeleton suspended in mid-air, levitating on his stomach, as if it was a whale in a natural science museum. Unlike Gino De Dominicis’ skeleton lying on the ground, Abdessemed’s is taking off like an airplane or a superhero, managing to escape the laws of gravity. “Habibi” then (‘much beloved’, in arabic) is the artist himself, a huge self-portrait, a very contemporary representation of vanitas.

“Habibi” (2004) – Adel Abdessemed

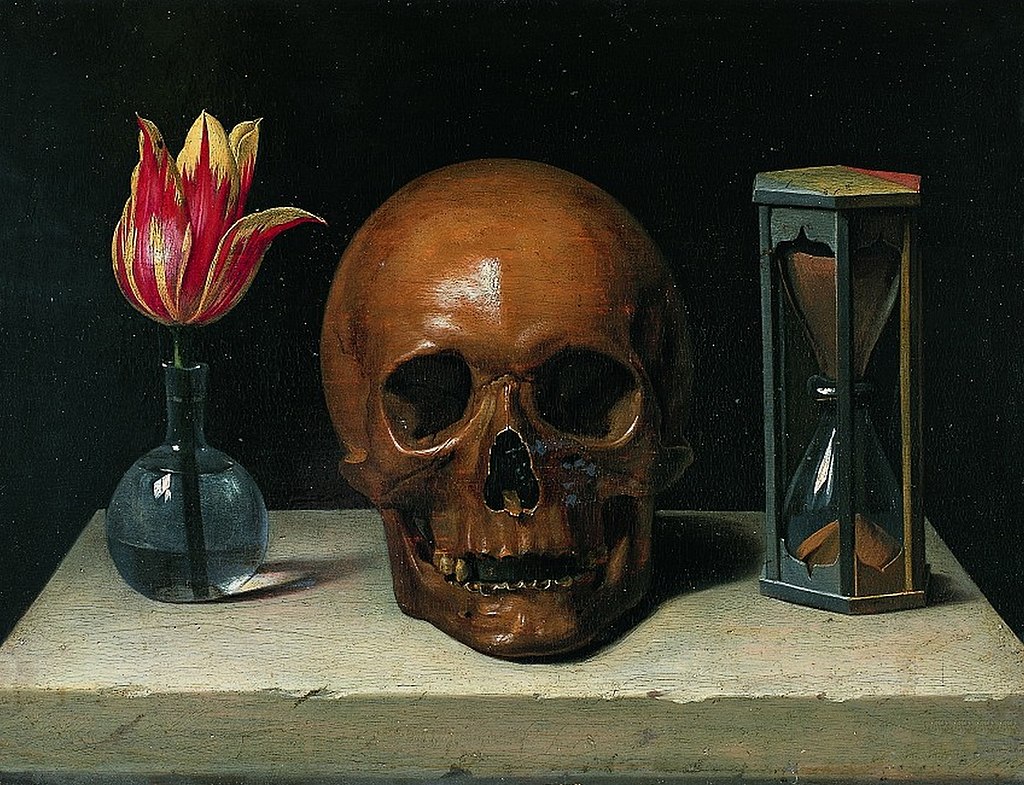

Some of the features of this philosophical idea have been universally represented in every historical period. An example may be the ‘still life’ of vanitas vanitatum of the Middle Ages and subsequent centuries, a reminder of the transient quality of earthly pleasures symbolized by the presence of the skull.

“Vanité, ou Allégorie de la vie humaine” (1644) – Philippe de Champaigne

The inclusion of the skull represents the brevity of human life (and especially the fact that death will touch us all, whether you are rich or poor) and its knowledge (compared to divine omniscience), but it is also a symbol of strong magical connotation, especially in Indian and Nepalese culture: see, for example, the skull wreaths worn by some Hindu gods such as Shiva or Kali or the Tibetan god Kurukulla. Death indicates – without a doubt – the ultimate end to the physical existence of the human being. Yet it is (perhaps) a transient state that leads to another form of ‘life’: resurrection, reincarnation, immortality through the transmutation of the soul.

All cultures base their existence on the dead ones: they talk to us from their tombs in books, dreams, legends, portraits, mausoleums and monuments. It’s their way of communicating the guidelines of our existence, to make the world and its rules understandable. The traces that we leave during our existence and after death inspire the work of several contemporary artists. The Swiss Olaf Breuning, puts dozens of skeletons or skulls in gardens or rooms as if they were expecting something.

“Skeletons” (2002) – Olaf Breuning

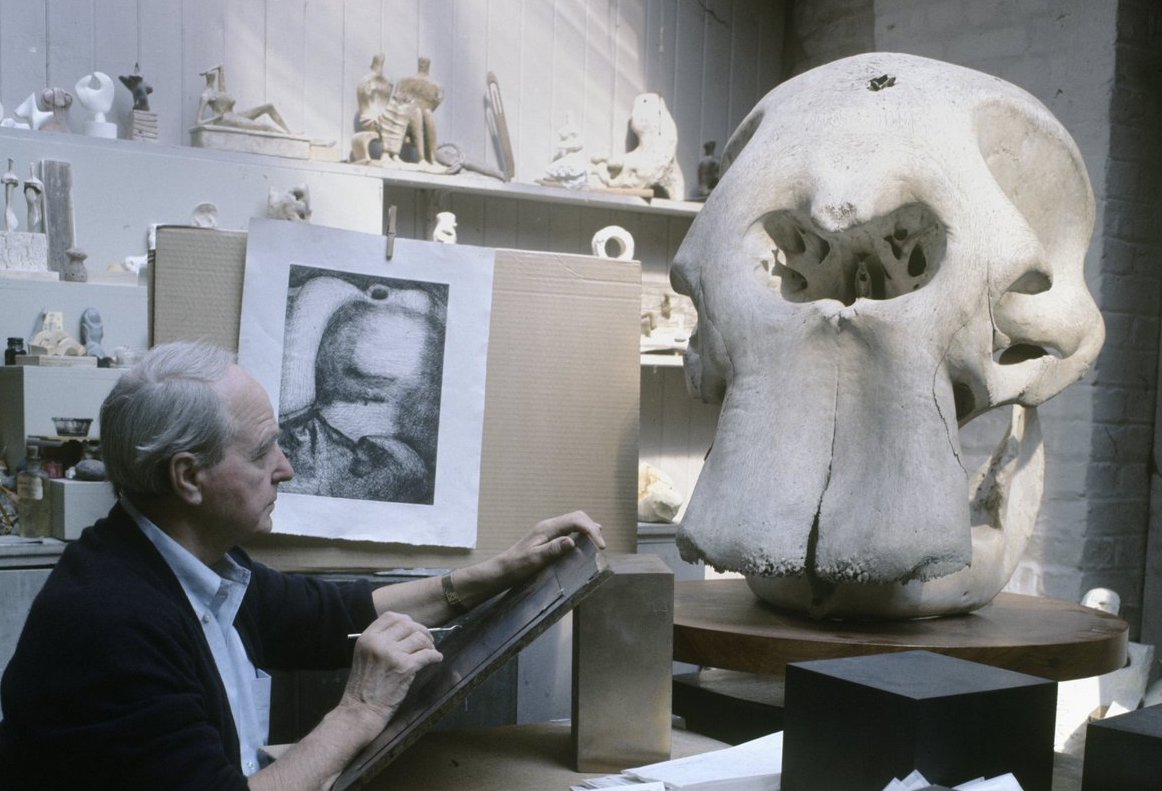

Marc Quinn uses blood and other materials to reflect on death, how life works, an about body mutability. One of the themes of his research is the preservation and maintenance of living forms, as when immersing flowers in frozen silicone (“Garden”, 2000); but it is undoubtedly known for works that have the subject of the human body and its deformities, such as the incredible skeleton of a man affected by phocomelia who lived in the second half of the eighteenth century: “Portrait of Marc Cazotte” (2006). These are works of art to enable a communication with those who have already died, to make people acquire familiarity with their own mortality, to take away the scary nature of death.

Artists, and not only them, have often sought the opposite of death in the passion of erotism. For example, Ana Mendieta, a Cuban-American artist who resumes the theme of “Morte e la Fancilla” (The Death and The Girl) in a Femminist key, lying naked above a skeleton as in “On Giving Life” (1975). She kisses it, owns it on a lush lawn to emphasize the naturalness of the act. You can literary make love with death – as well as with your fears.

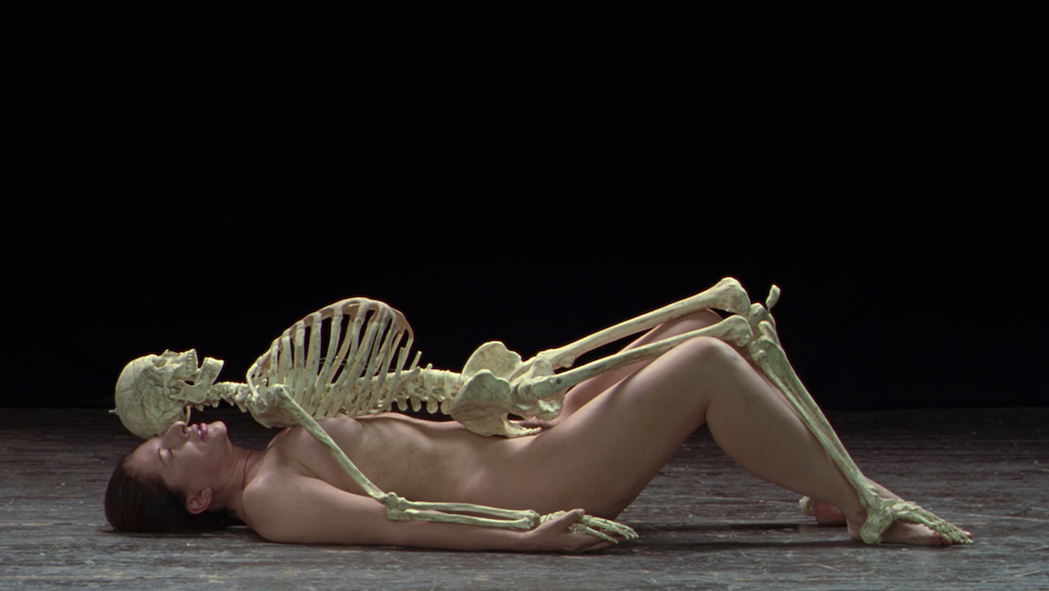

“On Giving Life” (1975) – Ana Mendieta

A theme ideally re-addressed by Marina Abramovic in her video-perfomance “Nude with Skeleton” (2005). The Serbian artist lies down naked with a skeleton on top of her. The living and dead body are almost perfectly aligned. The skull and Abramovic’ head look to the same direction. The ribs of the skeleton press upon her chest. Her breathing is accentuated and amplified. The skeleton’s spine, ribcage and head follow her movements while she inhales and exhales. According to Abramovic, the human skeleton is a metaphorical representation of «…the last mirror we will all face» , referring to death and temporality, which are recurring themes in her work.

“Nude with Skeleton” (2005) – Marina Abramovic

Another use of bones and skeleton in the Serbian artist is displayed in her most famous “Balkan Baroque”. In this work Abramovic presents a video showing herself brushing a heap of huge (animal) bones, which are then placed, once cleaned, in the museal space at the side of the screen. She proposes the idea of a body reduced to inanimate matter. The exhibition of the bones becomes relation between representation and fruition (by the spectator) of the horrid and the sublime. The horrid here plays a role of social criticism (Abramovic is talking about the horrors of ethnic war in the territories of the former Yugoslavia) as well as of transcendence, in relation to religion and the exorcization of death.

“Balkan Baroque”(1997) – Marina Abramovic

There so many examples of artists in contemporary art using, emphasizing, allegorising the “deadly theme” through the use of bones, skulls and skeletons. And there are plenty of skull representations in art history, from that depicted by the technique of Hans Holbein‘s anamorphosis in the canvas called The “Ambassadors” (or of the contemporary American artist Robert Lazzarini who makes them equally distorted and without any background), up to Andy Warhol’s serigraphs.

Mumoc (1976) – Andy Warhol

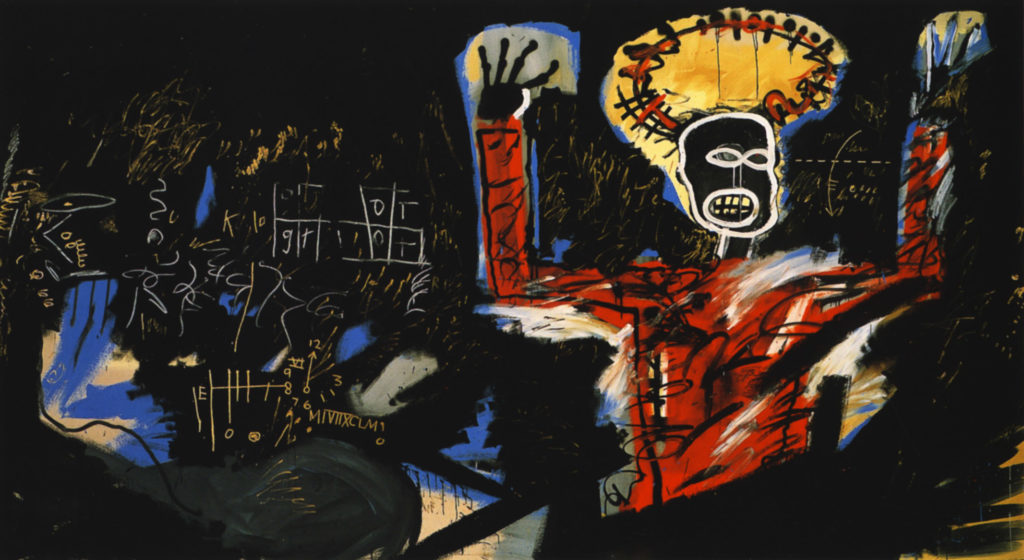

Skull and skeletons are also present in Warhol’s protégé Michel Basquiat‘s works , functioning as officiants and making accessible to the public his own Haitian cultural roots. He transforms himself in a shaman – in the hungan of the vodoo tradition –and his paintings are full of symbols, altars, skeletons and skulls, clairvoyant eyes, tools of the trade of the ‘medicine man’ to perform spells and inserted in a US metropolitan context, with continuous references to everyday life.

“Profit” (1982) – Jean-Michel Basquiat

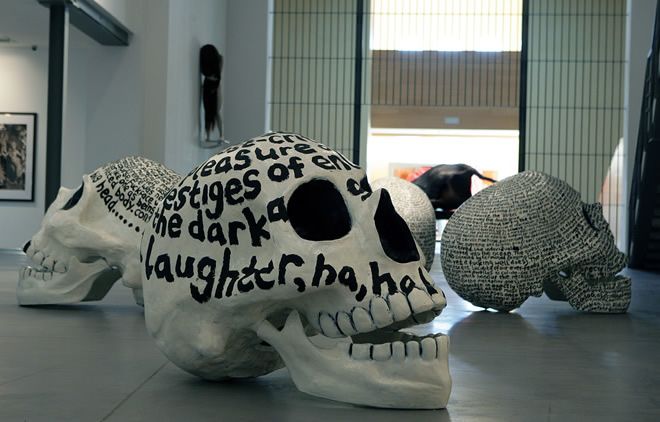

The iconoclast British duo Jake & Dinos Chapman often use skeletons and bones, as well as putrescent bodies, grotesque and teratological figures in their works for addressing topics related to death, war, horror and human destruction as in “Sneezy, Happy, Sleepy, Bashful, Snoddy, Grumpy, Dopey” (exhibited at art show Barrocos y Neobarrocos. “El Infierno de lo Bello”, 2005-2006). In this site-specific work, humongous skulls (120cmx70) – presumibly the leftovers of the seven dwarfs – are placed on the ground, each of them with their skull vault entirely covered with tattooed messages for the living. They become desecrating presences, surreal objects in which the spectator becomes part of the sculptural space.

“Sneezy, Happy, Sleepy, Bashful, Snoddy, Grumpy, Dopey” (2005-2006) – Jake & Dinos Chapman

In the seeminlgy human zoo art show “Mementum Moronika”, which neologism is based on the word “moron” to poke fun at the pathos of memento mori, the duo enact an ode to the idiocy of the world. The brothers illustrate that humanism, in the sense of the French philosopher George Bataille (whom they revere), is deceptive. They present the violent part of humanity, to recall that everyone is capable of tormenting others and thus carrying human reason to its grave. In this context skull-based works are inevitable: rotten, altered or deformed to address the fragility of human beings as “Famine” or “Migraine“.

“Famine” (2004) – Jake & Dinos Chapman

In Paolo Canevari the skull is instead used to denounce the desensitizing effect of mass media. In his video “Bouncing Skull”, one of the most emblematic and dreadfull works presented at the Venice Biennale 2007, surrounde by the apocalyptic scenario of the buildings bombed by NATO in 1999 in Belgrade, a child is playing football with what turns out to be a skull.

Thoughts run to other “famous” skeletons like those that populate the paintings and drawings of Otto Dix, an artist considered degenerate from Nazism who knew how to denounce in color and in black and white the tyranny, the war, the fears, the miseries and the human weaknesses, with nightmares on canvas that still have such an expressive force to cause an ethical catharsis in the observer.

“Meal in Sap trench” (1924) – Otto Dix

SKULLS EVERYWHERE: POP CULTURE, ART AND FASHION.

The representation of the skeleton grin and of slouching motility of the skeleton intrinsically hold the paradox of death celebrating life, similar to the carnival representations (Halloween), thus becoming a grotesque integral part of the daily anthropological panorama. It is not difficult to understand how, at some point in our history, the skull and the skeleton have become a symbol of challenge, dangerous living, of a provocation for its own sake, sometimes even losing the intrinsic value of spiritual research (as in fashion and paraphernalia).

Recent neo-baroque and neo-gothic artistic trends use the shape and image of the skull and skeleton by re-proposing them as anti-icon par excellence, since taboos of death and its representation have been overcome or modified. And so ‘skull-mania’ bursts, as fashion magazines call it. The pirate symbol has become a must: you can find it on big stars t-shirts and foulards, carried by teenagers on the neck and bags, reproduced in jewels of prestigious brands for ladies. There is a profusion of bones and skulls everywhere, even embroidered on shoes. As the contemporary speaks of inconvenient catastrophes, terrorist attacks, environmental disasters, wearing a deathly icon has a paradoxically skirmish value and an apotropaic function: it protects against dangers.

3D male/female skeletons graffiti over a building facate in Kreuzberg, Berlin.

The fascination with the image of the skull and the skeleton and other apocalyptic icons is not just a way to make love with death or make fun of the fear of mortality inherent in Western culture. Besides the obvious contrast between good and evil, it is a way to ironize on the dilated paranoia, to challenge an increasingly dominant, vigilant status quo. A challenge then used a lot by the subculture of heavy metal, punk or hard core bands that made the skull a public property, and also lucrative merchandise: flags, pins, t-shirts, stickers, etc. So from the 80s onwards the skull appeared in the streets, in fashion, in galleries, in all the possible and imaginable places on our planet.

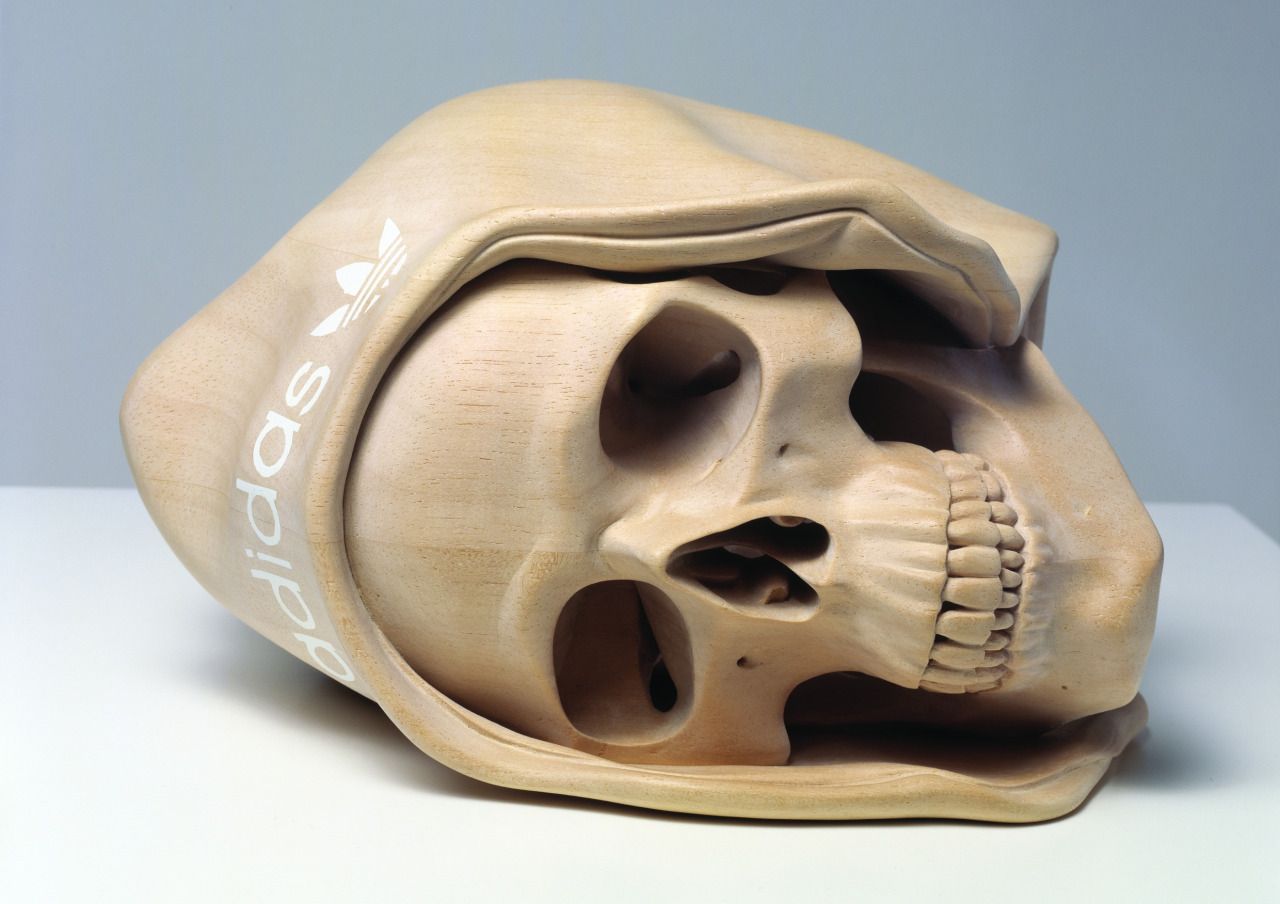

The Australian artist Ricky Swallow, for example, has chosen the icon of the skull as key object of pop culture, to make clear the uselessness of such human attachment to material things. A concept made clear in two of his works: “i-Man Prototypes” (2001), a series of highly colored resin skulls like Apple’s iMac G4 and “Everything is nothing” (2003), the ‘everything is nothing’ is made explicit by a wooden sculpture of a skull inserted in the hood of a sweatshirt of a brand of sportswear.

“i-Man Prototype” (2001) – Ricky Swallow

“Everything is nothing” (2003) – Rick Swallow

In the work of the Apulian artist Angelo Filomeno, suspended skeletons, embroidered in large shantung canvases, stand out in idyllic Renaissance landscapes or bright contemporary cities, with elaborate ornamental details. His visions are often linked to childhood marked by the loss of parents and they are born “often of sersa, when darkness leads to confrontation with thoughts and nightmares”.

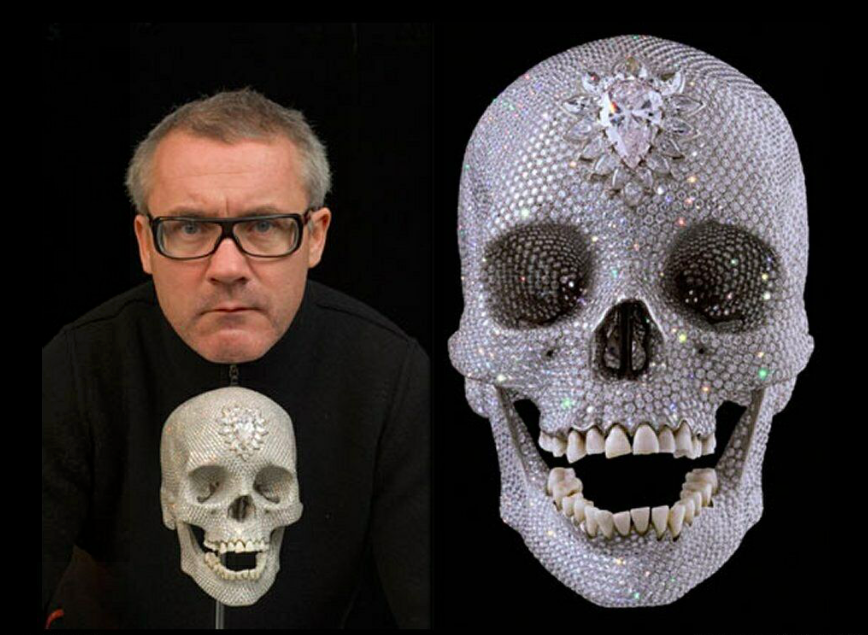

The skull became such a cliché in art that one can not speak of originality in its use, except maybe in the case of Damien Hirst’s most famous work “For the Love of God” (2007). Its exceptional cost and its magnificence make it indeed a unique work. It is the skull of an affluent society elaborated by its richest artist. Hirst dramatizes his bizarre position as an artist who has become immensely wealthy. He created something that no artist could ever create beforehand, one of those works that in the past were commissioned by kings to make their wealth and power evident, or as a gift or as a offer to deity.

Schermata 2018 08 29 alle 07.48.35

With this work Hirst communicates many things about the contemporary artist, art and religion. Even of the Western world, making it an archaic reminder of mortality and caducity. And it is at the same time a perfect masterpiece made of a platinum cast of an 18th-century human skull encrusted with 8,601 flawless diamonds, including a pear-shaped pink diamond located in the forehead that is known as the Skull Star Diamond.

If the traditional memento mori invites us to accept the universality of death, here the message is to leave a perfect body behind us, something virtually indestructible, of infinite durability, that can be the witness of the end of times. When the last breath of God will blow on the ashes of our world, this terrible object will continue to exist. A work that has embedded in our imagination and defines an historic moment, the emblem of decadence par excellence, a symbol of the madness of the art market (it was sold at about $ 100 million just before the world economy crashed).

THE VIVIFYING EFFECT OF DEATH AND HORROR

There is no civilization that does not consider death as part of life. Death and life are closely related, there is no one without the other. Thus skull and skeleton often become quotation, theatricalization, research, and exercise to exorcise death and to open to immortality: horror is in fact a fundamental complement to life and vitality. The bond between life and death in religion is strengthened by the rites of purification, including through the mutilation or destruction of the body.

So death laughs, dances, sings, plays and celebrates. In the propitious rituals of Aztecs, Incas or Voodoo, the concomitant presence of laughter and torture is commonplace. The idea of dismemberment of the incarnate god and of the skeleton and skull of the ‘chosen’ ones is also a common idea. And all this is resumed in the artistic representation.

In this context, it is emblematic the figure and the story of Rick Genest aka Zombie Boy who committed suicide at only 33. At the age of 15 he had been struck by a severe form of brain tumor. He was operated and miraculously healed. An almost dead, a survivor, a semi-god figure, besieged in the shadow of death itself that soon became his obsession. In a subtle play with the excess and the perverse, starting from age 21, he gradually turned himself into his worst nightmare, yet coiniciding with his most deviant dream, by tatooing 90% of his body with deadly themes and figures in a sort horror vacui triumph. As in a frightful tromp l’oeil, he had 136 human bones inked on his entire figure reproducing the structure of a skeleton mixed with internal organs and 176 specimens of insects. Also his once clean visage was “effaced” by a reproduction of a skull with the foldings of the brain faithfully drawn on the skull cap. An effect exploited by Oreal to advertise their products in a video that soon became viral.

Because of its unique appearance, living metaphor of the afterlife, our fears of death and wish of immortality, he soon became a fashion icon, a model courted by designers, photographers and pop stars as Lady Gaga who wanted him in his video “Born This Way“. As art critic and curator Helga Marsala puts it, in an Art Tribune article, Rick-Zombie boy became: “a ghost, a freak, a nocturnal creature forced into the light of day and exposed to the gaze of others, he combined provocation, lightness, macabre seduction, brazen irony, narcissism and a residue of shyness, a pathological intolerance and anxiety brought to the surface, to the extreme consequences.”

The spectator who observes the representation of death, deformation of the body, is the accomplice of his own death / resurrection and affirms – by contrast – his still dynamic and pulsing existence. This representation leads to a voyeuristic and even masochistic taste of the horrible and the disgusting experience. Almost a form, albeit low, of the sublime and of the push to spirituality and pathos. Horror has therefore a cathartic function: it is possible to approach the divine inaccessibility, thanks to the scary, horrible representation of the gods. The horrible and the macabre, in fact, attracts the gods.

Even Cervantes in “Don Quixote” describes the horror, in his role of vivifying, as a pleasure of death, as a re-activation of the senses, in the paradoxical culmination of pain for the loss of life that seems to be able to bring the subject back to its centre. Thus the bond between love, death, horror and initiation gives value to existence and becomes therapeutic.

Often the use of the skeleton or skull in arts is a way to empathically recognize or recall our futurist self. When the spectator sees the skull, he reflects on it, and in the reflection he perceives his own absent face. The skull is an empty mask and involuntary emblem of the aesthetic of the multitude. The emptied face mask is a post-human icon in which the spectator is abducted, enchanted, and chained. In a lot of iconography of the horror in painting, sculpture, in the photographic and cinematographic image, there is a pleasure in the visual enjoyment of the grotesque and the creepy.

There is no mistery that the taste for death, for horror, for the dark part of life is something that most contemporary artists reflect on and engage with. In fact, what place has the fear in today’s society? This Zeitgeist can give us a key to reading works of art that so often reproduce the symbols of terror with which we are bombarded daily by the media. Horror has become an accepted aspect of everyday life and art is simply a reflection.

The war on terror, death, and the culture of short-lived consumerism blend together are so ubiquitous that it is not surprising that they influence art. In his time, the Marquis de Sade by examining the work “Idée sur les Romans” affirmed that Gothic literature was the «inevitable result of the revolutionary shocks that the whole Europe had suffered». He then affirmed that the idea of the manifestation of horror in creative arts was an answer to a world made insensitive to violence.

Exploring the dark side helps to infuse a sense of security and control where society has lost it. And this artistic iconography reflects our struggle to keep an identity in a society that is losing its way. Horror is also associated with one of our primordial drives: voyeurism. The images of death and evil can be metaphor of art itself, that is, the uncontrollable desire to look. By watching violence or horror we become complicit in its creation, complicit of the cause, and so of the discomfort caused by the watch.

We know that humans are often those who cause terror, not certainly an imaginary evil external force. Actually its us who create our own nightmares. Better to remind it.